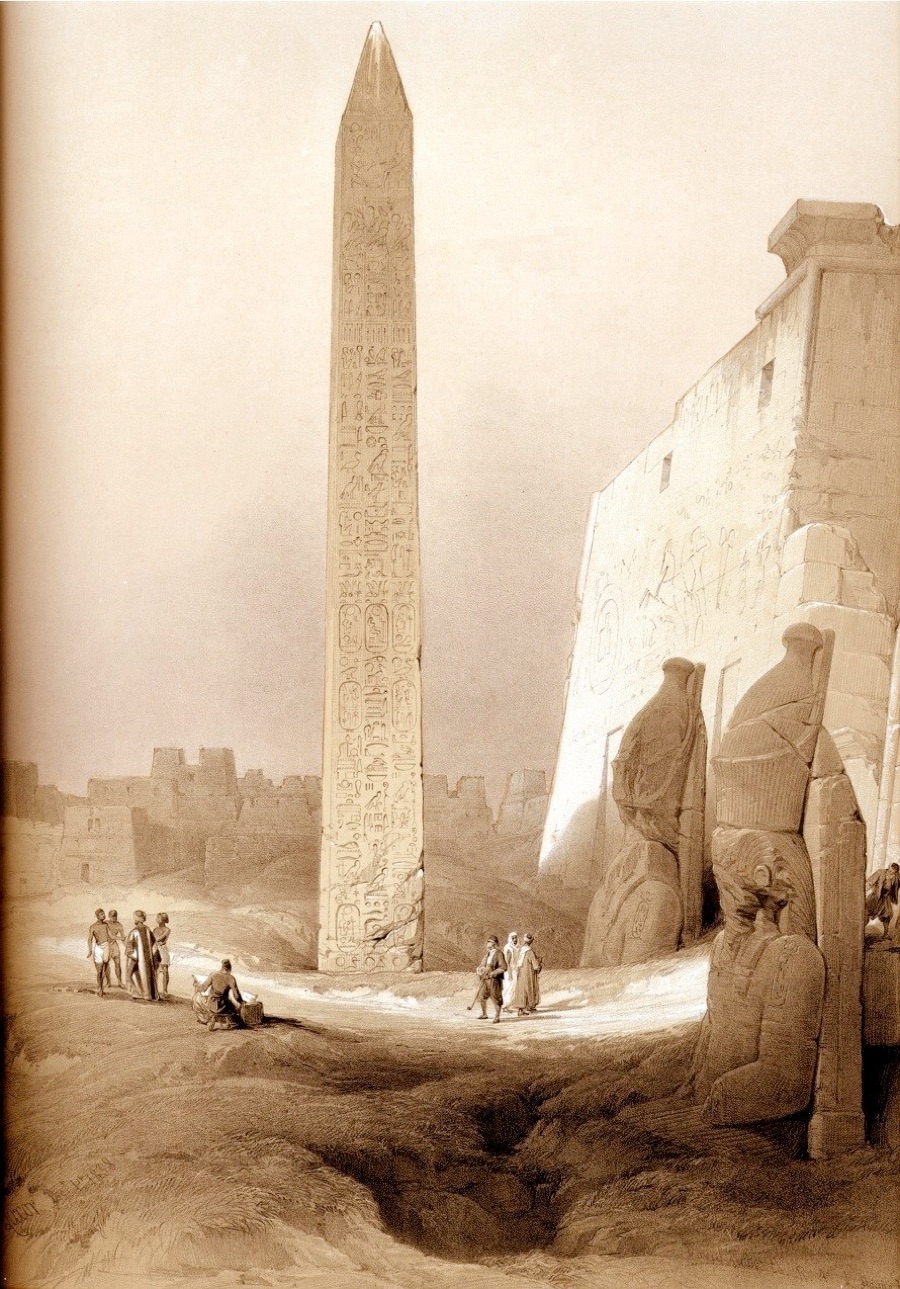

OBELISK AT LUXOR.

THE Temple of Luxor, which was originally raised by Amunoph III. B.C. 1507, appears to have consisted of a hall of enormous columns, a quadrangle, and the original Sanctuary in the rear. Fifty years later, and after two intervening reigns, Remeses the Great made those striking additions - the great court, the propylæ, the obelisks , and the colossal statues - which now collectively present one of the finest examples of the best age of Egyptian architecture.

Two stately Obelisks of red granite, profusely covered with hieroglyphics, admirably cut, and to a depth in many cases exceeding two inches, once stood before the sitting colossi which flanked the great entrance to the Temple; but the one on the right of the entrance has been removed by the French, and is now in the Place de la Concorde at Paris. “Being at Luxor,” says Wilkinson, “when it was taken down , I observed beneath the lower end, on which it has stood, the nomen and prenomen of Remeses II., and a slight fissure extending some distance up it; and, what is very remarkable, the Obelisk was cracked previous to its erection, and was secured by two wooden dove-tailed cramps, these, however, were destroyed by the moisture of the ground in which the base had become accidentally buried.”

The four sides of the Obelisks are covered with a profusion of hieroglyphics, commemorating, by grandiloquent inscriptions, this work of Remeses the Great. Of one of these Champollion has given the following abbreviated translation: - “The Lord of the world, Sun, guardian of truth, approved by Phra, has caused this edifice to be built in honour of his father, Amun-Ra; and has also erected these two great Obelisks of granite before the Ramseseion of the city of Amun.”

The horizontal section of these Obelisks is not rectangular, their faces having a slight convexity: the object of this was probably to render the front inscriptions more distinctly legible, for, as these face the north-east, they would, without this precaution, have been in shadow most of the day. If this were the motive, it shews the attention of the Egyptian Artists to local circumstances. M. Hittorf has supposed that the apices of the Obelisks were usually gilt: that they were gilt, or painted, or covered with metal, seems not improbable, for in ancient drawings on papyri the apex is distinguished by being black, while the side of the Obelisk is merely in outline.

The Obelisk which has been removed required a series of operations which employed five years, from July 1831 to October 1836, between its disturbance at Luxor and its erection in the Place de la Concorde at Paris; where it became the sixth object that had occupied or been prepared for the same spot within fifty years. A statue of Louis XV. was there during the old régime; a statue of Liberty (with the guillotine before it) during the Revolution; a column of wood during the Empire; which was removed at the Restoration, and arrangements made by Louis XVIII. to replace Louis XV.; but an order of Charles X. substituted a statue of Louis XVI. This was not, however, carried into effect before the Government of the last Revolution adopted the Obelisk of Luxor. The traveller who now looks upon the ruins of the Temple feels a deep regret that the completeness of its glorious façade should have been destroyed to gratify such a frivolous national vanity. The French obtained leave from Mohammed Ali to remove it; and erected it, at enormous cost, in their capital. Cui bono? - not to preserve it from destruction, not to commemorate a victory, or to mark an era in the history of France; but it was removed from its place of honour, where it had stood for thirty-three centuries, only to decorate, with the help of bronze and gilding, a spot in Paris which has been stained with thousand crimes.

Wilkinson’s Egypt and Thebes. Wathen’s Arts and Antiquities of Egypt.