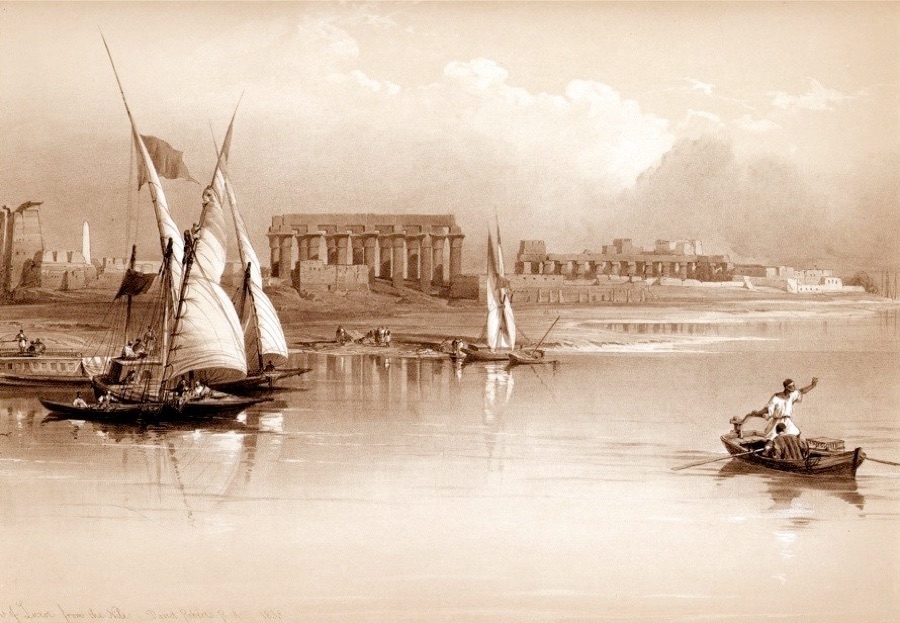

GENERAL VIEW OF THE RUINS OF LUXOR, FROM THE NILE.

AS the traveller ascends the Nile, on approaching Luxor, this striking view is presented of “the gorgeous palaces and solemn temples” of Thebes: they formed a part of that great city, unrivalled in vastness and splendour, which once filled the plain of the Nile from the Lybian mountains on the west to the bases of those of Arabia, the hills of the Thebaid, which bound the valley towards the east.

Every traveller who has ascended the Nile to the site of ancient Thebes has strained his eyes to get a first glimpse of its ruins - as the pilgrim to Rome gazes with eager devotion to catch the first appearance of the sacred fane of the St. Peter's. This feeling is gratified beyond all anticipation when the ruins of Luxor, El-Uksor, or the Palaces, open upon him - when the range of this glorious Temple is seen, stretching down a promontory of sand to the Nile, from its propylæ, through a forest of columns, to its Sanctuary which terminates the line of ruins near the banks of the river - a range of about eight hundred and twenty feet in length , but which at its eastern extremity is not accessible from the Nile. The flow of the river through Egypt from south to north generally takes a north-easterly course through the Thebaid, and the general direction through the Temple of Luxor from the propylæ to the Nile is S.S.W.

Large as these ruins appear, they form but an inconsiderable part of the remains of ancient Thebes: “they are only a fitting approach to Karnac.” The space which they occupy is, comparatively, so small that it is difficult to see its actual grandeur and conceive its diminished importance in relation to the City of One Hundred Gates. “As we look down,” says Warburton, “from these mountains (of Bibán El Malook), we discern on our far right the Palace of Medinet-Abou; before us, the Memnonium; on our left, the Temples of Gournou; then, a wide green plain, beyond which flows the Nile; and further still, on the Arabian side, Luxor rises its gigantic columns from the river’s edge, and the propylæ of Carnak tower afar off. This view scarcely embraces THEBES.”

On the ruins of Luxor, as on others of the vast structures of Ancient Egypt, houses are built and inhabited. Those seen above the columns of the pronaos were occupied by the officers of a French vessel during their operation of lowering and shipping one of the Obelisks, which formerly stood before the great propylon of the Temple of Luxor: its solitary companion is still seen in situ; and this view is taken from near the spot where lay the vessel by which the obelisk now in Paris was removed. The long wall and house which joins the two groups of columns is a granary, or shuna, of the Pacha, and the structure which is seen behind the propylæ is the minaret of a mosque. Under the columns, and in and about the Temple, are the huts and houses of the Fellahs and other inhabitants, which constitute the modern town of Thebes: among these are many Christians. Our holy religion was early established here from Ethiopia, and extirpated by the Moslem: the nucleus of a restoration may yet be found in the hundred families of Coptic Christians, who inhabit Luxor and have their place of worship four miles distant, on the borders of the Arabian Desert, where its services are administered by four priests. The moslem inhabitants live in wretched huts about twelve feet square, amidst filth and vermin; they are wretches who are said to have little enjoyment of life except what they derive from interrupting the enjoyment of others.

Luxor still holds the rank of a market-town; it is the residence of a káshef, and the head-quarters of a troop of Turkish cavalry.

Bonomi’s Notes. Wilkinson’s Egypt and Thebes.