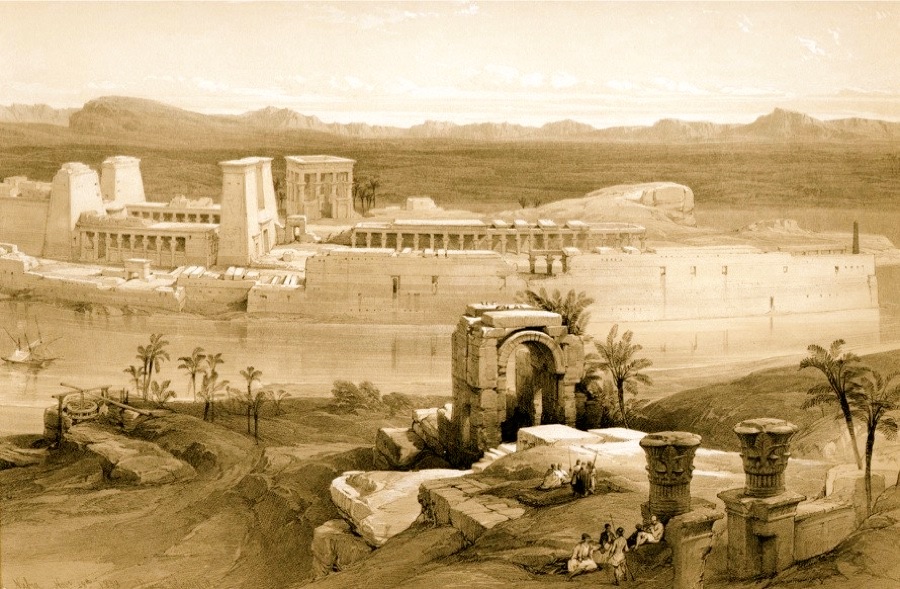

GENERAL VIEW OF THE ISLAND OF PHILÆ, NUBIA.

PHILÆ is at the head, and is the most eastern of the group of islands and rocks which form the First Cataract of the Nile; and the traveller who has ascended the river and reached Philæ, has passed this dangerous navigation and entered Nubia. Philæ is known to the natives as Giesirel el Berbe el Ghassir - the Island of ruined Temples. “It is,” says Roberts, “a paradise in the midst of desolation. Its ruins, even at a distance, are more picturesque than any I have seen. To me it brought recollections of my fatherland - I know not why: I thought of the first descent upon Roslin Castle; though there are no points of resemblance, except, perhaps, in the high and barren rocks, which nearly surround Philæ, to remind me of Scotland.”

This view embraces the whole of Philæ from the neighbouring island of Biggè, taken from a spot on the high rocks near some ruins. Its length is about five or six hundred yards. Warburton describes the whole island as not being more than fifty acres in size, but as richer, perhaps, in objects of interest than any spot of similar extent in the world. The prospect extends over an assemblage of temples, and the islet, amidst rich verdure, is strewn with marble wrought in every beautiful form known to ancient art; over prostrate columns palms are waving, mingled with the foliage and blossoms of the acacia. Around the island flows the clear, bright river, and on its brink lies the old temple of Osiris, now called Pharaoh's Bed; beyond the river green patches dispute the surface with the drifts of desert sands, palms, rocks, and villages; beyond all, and darkly encircling this paradise, rises the rugged chain of Hemeceuta, or Golden Mountains.

The Island of Philæ was esteemed the most sacred place in the dominions of Egypt. Here their mythological legends placed the tomb of Osiris; and when they swore - by him who slept in Philæ, - they gave to their oath its greatest solemnity. The island at large was consecrated to the great triad - Osiris, Isis, and Horus; but the principal temple is supposed to have been dedicated to Isis. Walls and embankments of great strength have been built on the rocky shores of the island, forming strong defences against the river, or an enemy, and presenting a larger levelled surface for its sacred structures. The principal water-gate is seen on the left, which leads to the inclosure. Mr. Hay, it is said, has discovered a subfluvial tunnel or passage between Philæ and Biggè, composed of well-constructed masonry, into which the entrance from Philæ led by a shaft found in the ruins of the Great Temple.

The Island of Philæ was the boundary of the conquest of the French army in Egypt. Desaix, who commanded the first division, pursued the Mamlouks beyond the Cataract, and left an inscription on the doorway of the great pylon at the end of the avenue to record the event: it bears date the “13 Ventose, 3 Mars, An 7 de la République, de Jés. Chr. 1799.” How is it that no Englishman, with the scribbling propensities of which he is so often accused, has yet added to this record, - Expelled from the land of Egypt by an English army, September 2d, 1801?

Warburton tells an amusing story of Stevens, the American traveller, whose appreciation of the perfections of his own country is considerably at issue with that of any other, giving us an imposing account of the feelings with which he carved his name on the same slab with that of Desaix. A French traveller followed, who, thinking it bad taste even in an American thus to intrude the name, carefully eradicated it, and inserted, “La page de l’histoire ne doit pas pas être salie.”

Roberts’s Journal Warburton’s Crescent and the Cross.